20 Years from Now We May Sorely Regret Building All of These Glass Towers

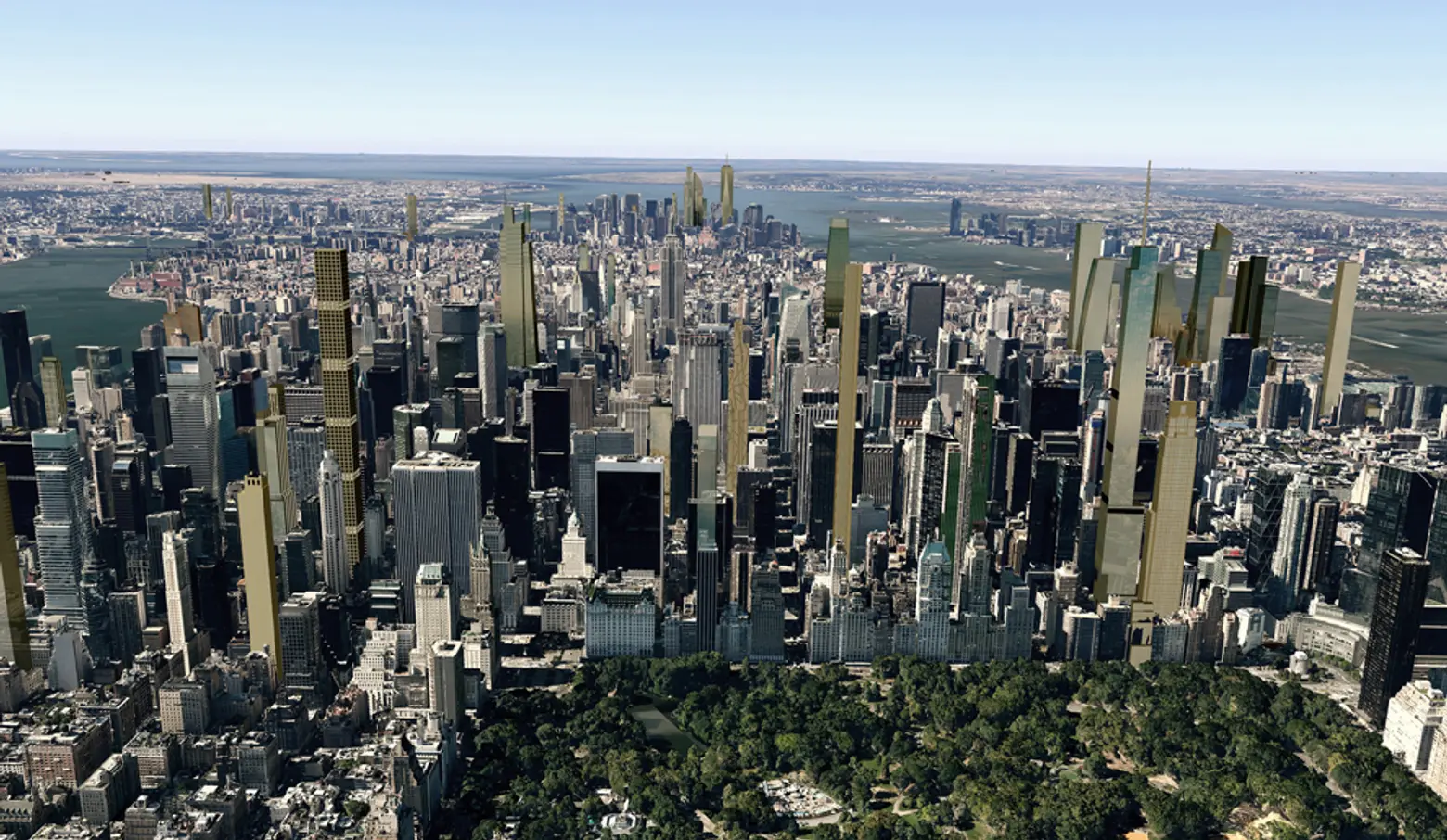

What Manhattan will look like in 2018. Many of the buildings going up will be wrapped in glass. Image via CityRealty

Providing more affordable housing to New Yorkers is at the top of the De Blasio administration’s agenda, but greening the city is certainly a major concern as well. It is anticipated that a new bill aimed at cutting the city’s greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050 will be signed in to law, much of which is expected to center on green building. Ambitious, yes—but is 2050 too late? The Globe and Mail recently interviewed Canadian architect and journalist Lloyd Alter on the glass condo obsession, which, as with NYC, is taking the cities of Vancouver and Toronto by storm. What Alter shares for the future of glass towers worldwide is quite bleak, but he also proposes a number of measures and case studies that NYC developers should certainly take note of if they want to reduce costs and keep property values up in the long run.

For tall towers, glass is the biggest obstacle for energy-efficiency. Today, windows are no longer built into walls; instead, they make up entire walls. Unfortunately, glass has a low insulation value (equivalent to just a couple of sheets of cardboard, says Alter) and its transparency causes buildings to overheat in the summertime, while in the winter, areas near it are often cold and uncomfortable. Many people who live in glass buildings can attest to this, and, interestingly, though many of us are seduced by the look, according to a recent study conducted by the Urban Green Council, the majority of people who live in glass towers keep their shades drawn.

It seems like there’s no stopping the all-glass trend, but there are parts of the globe catching on to the fact that it is not sustainable in the long run. Alter cites the province of Ontario where windows can no longer make up more than 40% of a wall unless developers opt for energy-efficient glass that has been treated (typically with argon gas between two sheets of glass) to increase insulation. But he notes that even with better-insulated glass, which can be prohibitively expensive, after 10-15 years, the argon gas sandwiched between the two panes eventually leaks out, ultimately requiring replacement.

For any given building, he says, “What you’ve got, I believe, in 15 to 20 years, is a very cold, drafty, leaky building that you can’t afford to heat or cool anymore…I think what’s going to happen is that they’re going to put a lot of money into those reserve funds, and there are going to be a lot of assessments, and in 15 years people are going to be paying a lot of money to re-clad those entire buildings.”

Alter stresses that developers worldwide need to be concerned with energy, comfort and health. He cites several projects in Canada, but says we should really look to California, a state that’s long had maximum glass rules due to environmental challenges related to overheating and air conditioning use, and the Germans who, for example, have thermal break codes for balconies. Watch the video above to find out more.

[Related: More Green Buildings Likely Under NYC’s New Greenhouse Gas Plan]

[Related: Glass Towers to Go Green? Environmentalists Are Calling for Stricter Regulations for Supertalls]

[Via The Globe and Mail]