100 years ago, Hanukkah was a brand-new holiday to New York

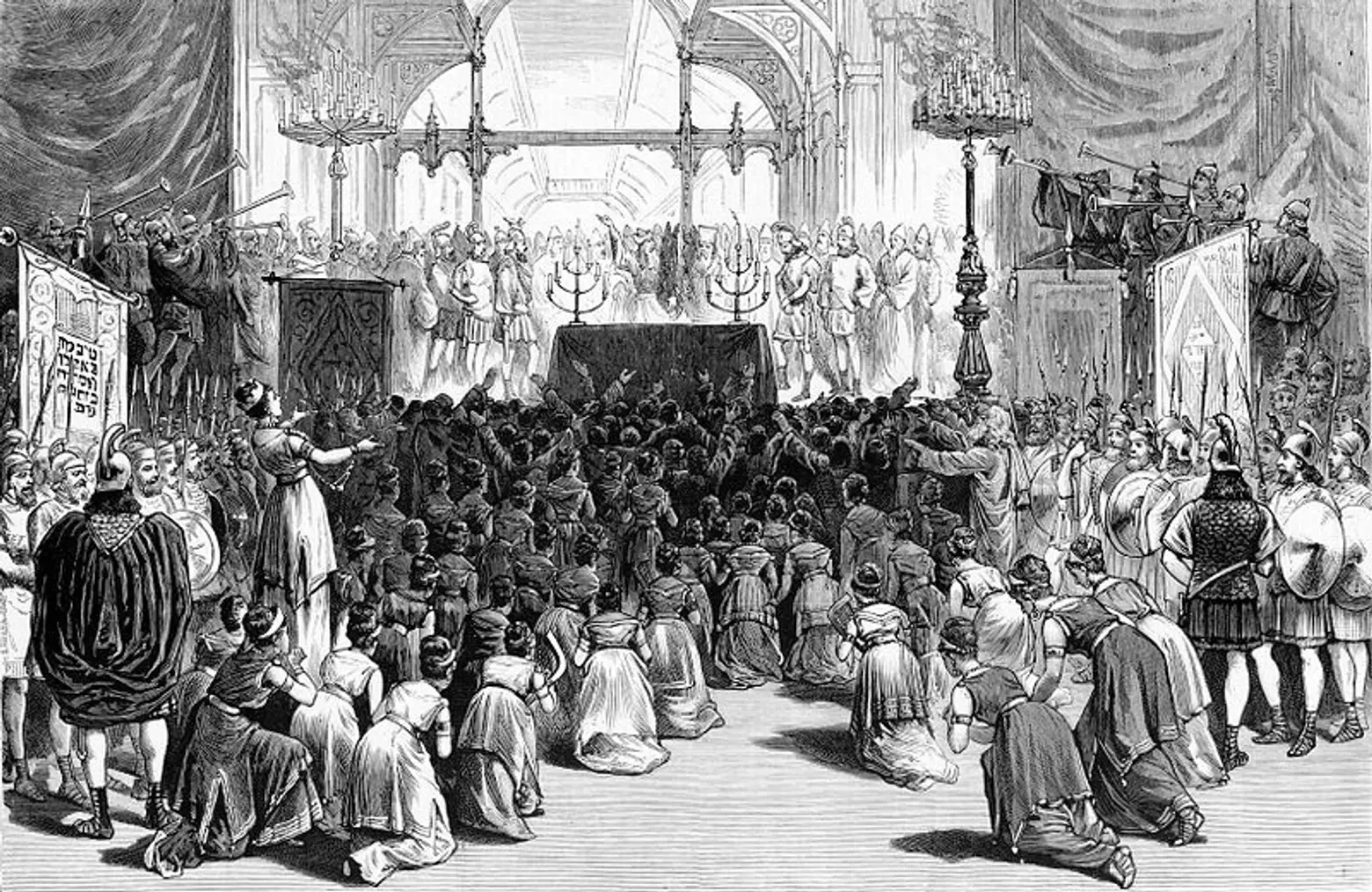

Hanukkah celebration by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association at the Academy of Music in New York City, 1880, via Wikimedia Commons

Hanukkah is engrained into New York’s holiday season, but roughly 100 years ago the Festival of Lights was big news to many New Yorkers. Look at the newspaper coverage back in the day regarding the holiday, and most “took an arms-length approach,” as Bowery Boys puts it. “More than one old Tribune or World carried a variant of the headline “Jews Celebrate Chanukah,” as though there might have been some doubt. A 1905 headline even informed readers that, “Chanukah, Commemorating Syrian Defeat, Lasts Eight Days.”

Such headlines weren’t just the result of ignorance–New York’s Jewish population was low through the 1800s, and even within the religion, Hanukkah has traditionally been a minor festival. But a boom in Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe and a reassertion of religious traditions in a new country completely changed the fabric of New York. Eventually, the eight-day festival of light–which commemorates the victory of the Maccabees over the Greeks over 2,000 years ago–emerged as an important tradition of the city.

In a December 1894 edition of the New York Sun, an article simply asked, “Christmas or Chanukah?” At the time, New York’s Jewish population was quite low, with 250,000 residents living across the entire United States by 1880. And Hanukkah was not yet considered a major celebration of the faith. A prominent rabbi from Temple Emanu-El told the New York Sun that he “rebukes the tendency of Jews to confuse the festivals.”

Still, New York’s Jewish population recognized the holiday, albeit modestly. According to the Tenement Museum, “Passengers riding the elevated train through the Lower East Side on a December night in the 1890s would have seen hundreds of tiny candles illuminating the windows of tenement apartments inhabited by Eastern European Jews.”

But the first Jews to promote Hanukkah in America weren’t in New York, according to the Atlantic. In the middle of the 19th century, rabbis who led the Reform Movement, largely based in Cincinnati, Ohio, came up with the idea of a “festival of lights” for children at Hanukkah as a way to keep them interested at synagogue. Taking the celebration home tied to a growing trend of home-based celebrations, like birthday parties, happening across the country in the second half of the 19th century.

The early 20th century would change the fabric of New York, bringing mass immigration of Eastern European Jews to New York City. Though New York was a Christian-leaning city, these immigrant communities were living in a country that held its promise of freedom of religion. And so a debate started in how Jewish traditions would live on not just in New York, but the country as a whole. As the Tenement Museum puts it, “Hanukkah offered an opportunity for many Jewish immigrants to openly celebrate their religion—something that wasn’t always possible in their countries of origin.”

Still, celebrating Christmas and assimilating to the new culture proved appealing to many newly-arrived immigrants. The New York Tribune noted on Christmas Day, 1904, that “Santa Claus visited the East Side last night and hardly missed a tenement house.” Jews installed Christmas trees in their homes and thought nothing of the carols their children sang in the public schools, according to Slate.

Others looked at the commercialization surrounding Christmas with hesitation. Many Jews had “a deep and abiding anxiety about Christmas—this commercialized, merry, fun, sparkly Christmas was altogether new to them,” Jenna Weissman Joselit, a professor of history at George Washington University, told The Atlantic. And Jewish leaders had become concerned that their religious traditions would be abandoned to those quickly acclimating to New York City.

Hanukkah, in effect, emerged to serve almost as a counter-balance to Christmas. For many immigrants and their children, the celebration became a way of asserting Jewish identity in America. And as more and more Jews found economic success in New York, buying presents for children became a way to validate the risk they took in emigrating. Ultimately the Americanized holiday was the effort of those “who felt the complexities of American Jewish life most acutely,” as the Atlantic put it.

As the 20th century wore on, the Hanukkah industry emerged, the celebration became more widespread, and the confused newspaper articles were long gone. By the 1970s, menorah lightings were taking place in American parks, city halls, and village greens. By 1979, President Jimmy Carter was participating in a lighting ceremony. Today in New York, the Chabad-Lubavitch Jewish outreach organization sponsors the lighting of a massive menorah, 32 feet tall, on Fifth Avenue and 59th Street near Central Park.

It’s worth mentioning that Jewish New Yorkers also shaped the Christmas season as we now know it. A young Russian Jew, Irving Berlin, was trying to make it big through the early 1900s in Tin Pan Alley–he would go on to write “White Christmas” in 1943.

Jay Livingston and Ray Evans wrote “Silver Bells” after being inspired by the Salvation Army bell ringers around the city. But the fascinating history of the Festival of Lights here in New York is an example of how immigration and traditions from elsewhere have come to define the city’s holiday season.

RELATED:

- The 10 best holiday events and activities for NYC history buffs

- A guide to 2017’s holiday window displays in NYC

- In 1882, Labor Day originated with a parade held in NYC

Editor’s note: The original version of this story was published on December 8, 2017, and has since been updated.