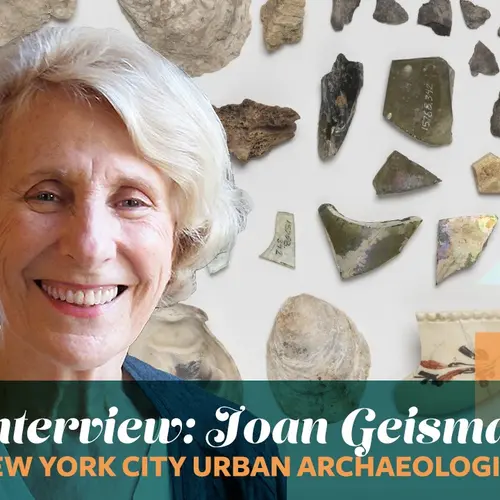

INTERVIEW: Urban archaeologist Joan Geismar on the artifacts she’s dug up across New York

Joan Geismar boasts a job that’ll make any urban explorer jealous. For the past 32 years, she’s operated her own business as an archaeological consultant, digging underneath the streets of New York City to find what historical remnants remain. Her career kicked off in 1982, with the major discovery of an 18th-century merchant ship at a construction site near the South Street Seaport. (The land is now home to the 30-story tower 175 Water Street.) Other discoveries include digging up intact remnants of wooden water pipes, components of the city’s first water system, at Coenties Slip Park; studying the long-defunct burial ground at the Brooklyn Navy Yard; and working alongside the renovation in Washington Square Park, in which she made a major revelation about the former Potter’s Field there.

With 6sqft, she discusses what it felt like unearthing a ship in Lower Manhattan, the curious headstone she found underneath Washington Square Park, and what people’s trash can tell us about New York history.

Burial vault unearthed beneath Washington Square Park, via Department of Design and Construction

Archeology hasn’t always been a part of the city’s DNA. Many New Yorkers long assumed there wasn’t much history preserved underground. But in 1978 New York passed the City Environmental Review Act, requiring government agencies to consider the environmental impacts of construction projects utilizing public funds. That meant bringing an archeologist on site, many of whom discovered artifacts within the landfill of Lower Manhattan. In the 1980s, the Landmarks Preservation Commission added an archaeologist to its staff to oversee archaeological work at landmarked sites.

Geismar calls this time, just as she began her career, “the golden age of archeology in New York City.” Since then, the LPC has curated thousands of archaeological artifacts found throughout the city, ranging from thousands of years ago to the 19th century. Despite pushback from developers–often less than enthused to accommodate archeologists at their construction sites–Geismar has proved the necessity of exploring New York’s underground history.

Let’s start with how you got into this field.

Joan: Serendipitously. When people learn I’m an archeologist, their faces often soften and they say, “That’s what I wanted to be as a kid.” That wasn’t me, I never even dreamed of archeology. I was an English major in college, then worked at Random House Publishers before getting married.

But after being married and with three small children, I realized I needed something more. My husband, a graphic designer, was preparing an exhibit about Native Americans in the U.S. and their art. So I started reading books he left around the apartment, and the Native American art fascinated me. I thought I’d bite the bullet and go back to school.

I applied to the art history department at Columbia and I was accepted. I realized, though, it wasn’t the art, it was the people I wanted to know about. And the only way to get to those people was through archeology, so I switched to anthropology.

And did you know you wanted to practice archaeology here in New York?

Joan: I had to. With a husband and three little kids, I couldn’t pick up and go somewhere. I was offered a site, on the Palisades of New Jersey as my dissertation site. It was a historical site that turned out to be a community of freed slaves. It was part of the Columbia University Field School and nobody was doing anything with the material. I truly agonized over this site and whether I should study it, thinking that I’m not a historian. But I did it–it intrigued me and I love history. So I became a historical archeologist and when I finished my dissertation I got a job instantly in New York. This was when archeology was happening in New York City.

Tell me about that time, when archeology was happening in New York.

Joan: In the late 1970s, there was a site in Manhattan known as the State House site. I was still in graduate school then. It was the first big site where archeology became an issue because of new environmental laws, and it proved there was archeology in Lower Manhattan. People thought, “how could there be anything left with all the building gone on?” Well, it turned out there was a lot left.

Because of this site, the Landmarks Commission got involved. The State House was the first test the new City Environmental Quality Review Act. It meant the city had to consider environmental issues when there was public money involved.

In the early 1980s, which is when I got my degree, I think of it as the “golden age of archeology” in New York City. There was so much excavation going on in Lower Manhattan, where there is so much potential for archeology.

What was your first big New York City site?

Joan: 175 Water Street, which turned out to be a phenomenal site. It was the entire city block in the Seaport area. That was where, as someone said, “Joan, your ship came in.”

It was by accident we found this ship. We were testing to see how deep the landfill was. Something was holding the earth in, or we wouldn’t have had the block. It turned out, in this instance, it was in part a 100-foot ship. When we first started digging, the dirt fell away and exposed wood planks. I thought it was cribbing [used to hold the landfill in], but it turned out it was the midsection, portside, of a derelict 100-foot merchant vessel.

The ship uncovered at 145 Water Street, courtesy Joan Geismar

The ship uncovered at 145 Water Street, courtesy Joan Geismar

So what happens after you discover something like that?

Joan: Well, can you imagine the excitement of finding something you never expected to find? We do research before we go into a site. That alerts you to what you may or may not find. In this particular instance, there was wonderful research done by a historian, but no hint of there being a ship.

Everything we find is exciting, just the act of discovery is thrilling. Even when we find a teapot, it’s wonderful. It’s something that belonged to someone else a long time ago, and it’s a clue into their lives.

New Yorkers don’t always realize all the artifacts that are still underground.

Joan: Landfill sites were a convenient way to get rid of trash, so that’s where it went. And when New York didn’t have plumbing, there were backyard sanitary facilities. That would be the privy, which is the outhouse, and a cistern, or a well for water. When indoor plumbing became available, those holes or pits were filled. They are archeological treasures because the privy was a convenient place to throw things. Although, when no longer in use, they were supposed to be filled with clean sand, that’s not what people did. People never change. The first four feet were often cleaned and sanded, but below that was trash. That’s what tells us about people’s lives.

A tenement privy, courtesy the NYPL Digital Gallery

A tenement privy, courtesy the NYPL Digital Gallery

When you dig something up, how do you use it as a clue to how people lived their lives?

Joan: You look at the artifact, which tells you what was available and tells you what they chose. What I’ve discovered, looking at the deposits in numerous privies, is that each privy has its own character. Personal trash really is very personal.

What do you typically pull up from the privies?

Joan: If you have a 19th-century site, which is most of what we get in Manhattan, you get ceramics–what people ate from–and animal bones–what people ate. Soil analysis will show you what kind of vegetables and fruits they ate. The trash didn’t always belong to the family, sometimes it was brought in as fill. But around the edges, and at the bottom of the privy pit, those residues are usually connected to the family that used the privy. And it tells you a lot about people’s lives. I know that middle-class people at a privy in Greenwich Village had intestinal parasites, besides beautiful china.

I’ve also worked where there aren’t these kinds of features. One of my recent projects was at Washington Square Park, where I was on and off for nine years during the renovation. I could only look where they were doing work–so if they were putting in a new waterline, that’s where I had to be.

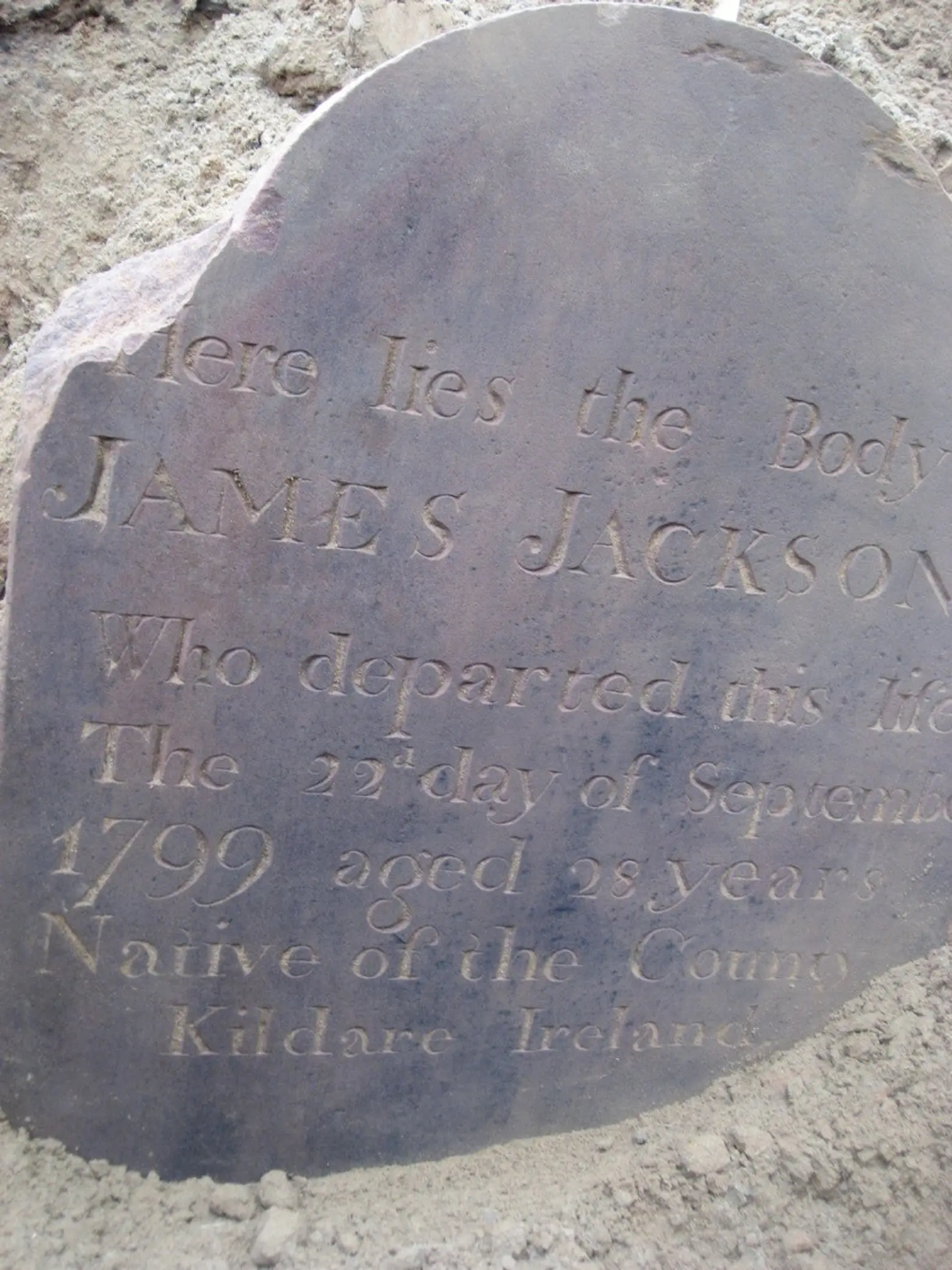

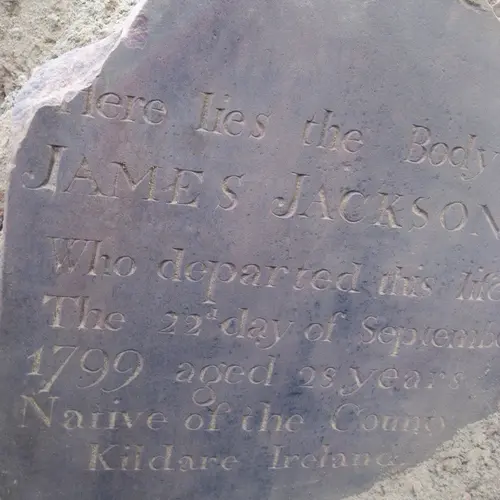

The reason I was there was because two-thirds of Washington Square Park was a Potter’s Field from 1797 to 1825 and the question was if the human remains were ever removed. It was where the unknown and the poor were buried. But that’s not exactly what it turned out to be. One thing we encountered was a very simple, beautiful tombstone. That was shocking, a headstone in a potter’s field? It was the headstone of James Jackson, who died in 1799 at the age of 28 from County Kildare [in Ireland]. With that information, I learned he died of yellow fever. Everyone was terrified of yellow fever and thought it was highly contagious. In an old newspaper online–dated two weeks before Jackson died–I found a postscript that anyone who died of yellow fever had to be buried in the potter’s field to avoid contagion. So it changed the entire concept of this particular Potter’s Field. It wasn’t just the indigent and unknown, it was also all those who died of yellow fever late in the summer of 1799.

The headstone of James Jackson, courtesy Joan Geismar

The headstone of James Jackson, courtesy Joan Geismar

So how do archeologists end up on landmarked sites?

Joan: A number of years ago, I had a site in Greenwich Village. The reason I had it was because the owner of the property wanted to put in an underground garage. Because he needed a permit, that opened a review process and the Landmarks Commission said he needed to consider archeology. That only happens under certain circumstances. But if this work didn’t require a special permit, we’d never know what they had in that backyard.

Is the stuff you dig up preserved, or does it go back underground?

Joan: The relics don’t get covered back up, the site gets covered back up. And everything we find gets documented. For example with the ship, every plank was drawn and photographed. The planks were then carted off to the Staten Island landfill, Fresh Kills. But the bow has been disassembled and swimming in polyethylene glycol at the maritime museum for all these years. Theoretically, it could be reconstructed.

For city-owned properties, there’s a brand new repository called the Nan A. Rothschild Research Center for artifacts from NYC-owned properties like parks. They have quite a collection.

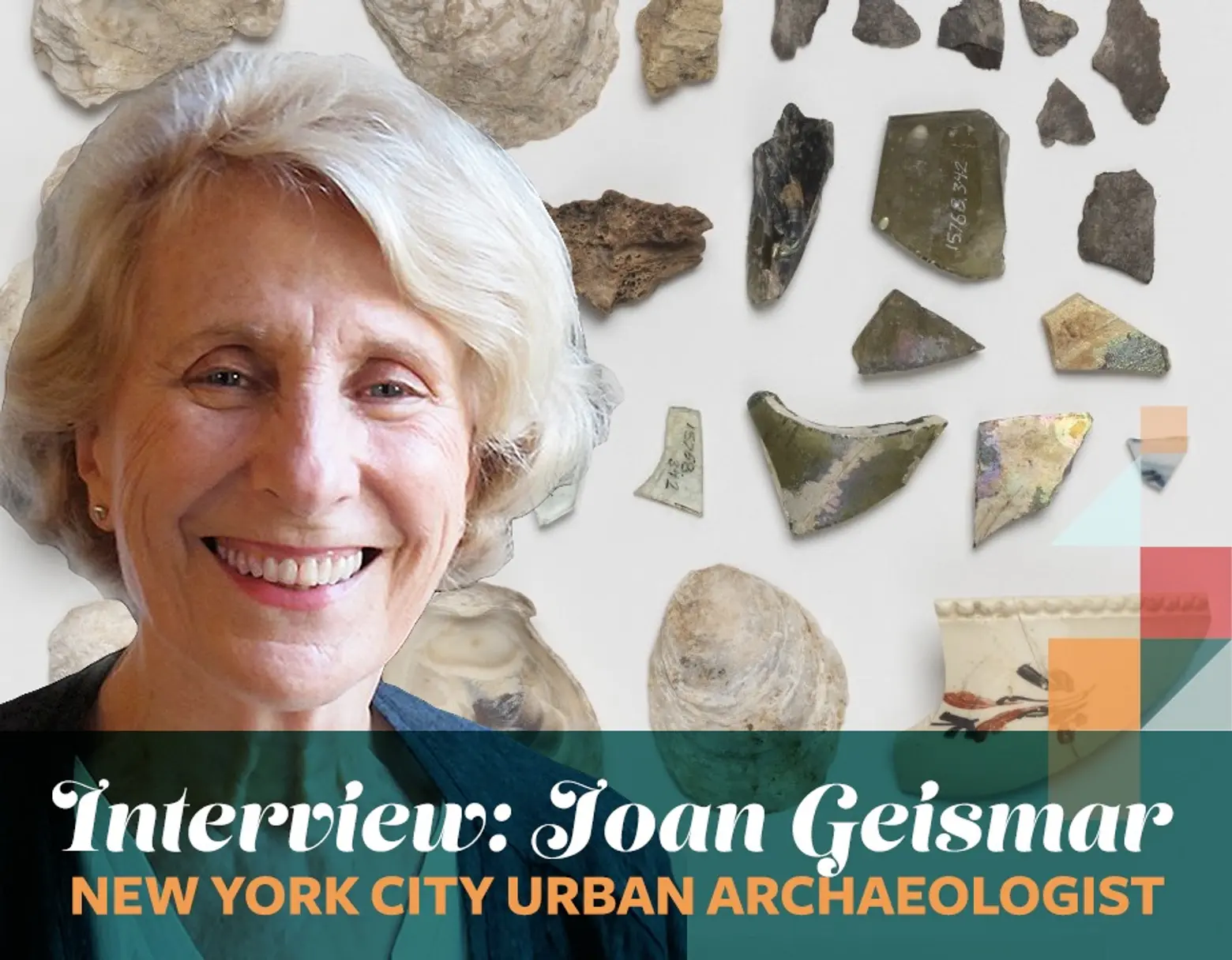

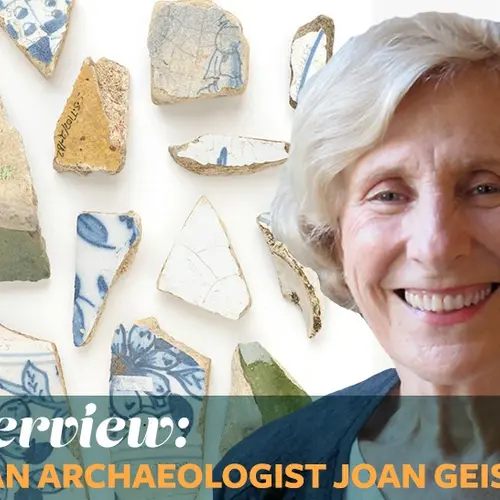

Relics preserved at the Nan A. Rothschild Research Center, courtesy of NYC Archaeological Repository

Relics preserved at the Nan A. Rothschild Research Center, courtesy of NYC Archaeological Repository

How would you characterize archeology right now in New York?

Joan: The attitude toward it has gotten better, I think, but developers don’t like us. We’re a thorn in their side, and we have a terrible reputation of holding things up. But it’s not true. If they think ahead, we hold nothing up. At 175 Water Street, where the ship was found, I have pictures of us doing archeology as they were testing their piles for the building.

The ship excavation, in oval, during construction. Courtesy Joan Geismar

The ship excavation, in oval, during construction. Courtesy Joan Geismar

Have you had any big discoveries recently?

Joan: Now, I’m working at a NYCHA site in Gowanus. We’re looking to see if there’s anything left of mid 19th-century backyards on this site, where NYCHA built fourteen buildings were built in the 1940s. I looked at photos of the construction site and saw trees–I don’t know whether they are street trees or backyard trees. If they’re backyard trees, it means elements of the backyard, and their cisterns and privies, may still remain.

We’re testing there now. I haven’t found anything spectacular yet, but I have found remnants of mid 19th-century life that remain. My research shows this had been very wet land and in the 1830s, it was filled in to make it liveable. What I’ve found, so far, is a stone drain that I assume helped control water the backyard in a landfill situation and probably was very wet.

It’s nothing spectacular, but it’s evidence of life in the past. It remains, despite all this construction. To me, it again shows that archaeological features can be remarkably tenacious.

RELATED:

Get Insider Updates with Our Newsletter!

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

If there are any urban geologists out there:

they should take a look at the line of huge boulders, presumably pushed down from Canada at the edge of a a recent ice age terminal moraine. They can be seen lined up (via bulldozers) just off Kent Avenue in Brooklyn where the former oil terminal on the East River is being slowly transformed into Bushwick Inlet Park. I’ve seen similar ones in constuction sites a few hundred feet south alongside Kent Avenue as well

As Trump is fond of saying; they’re huuuge.