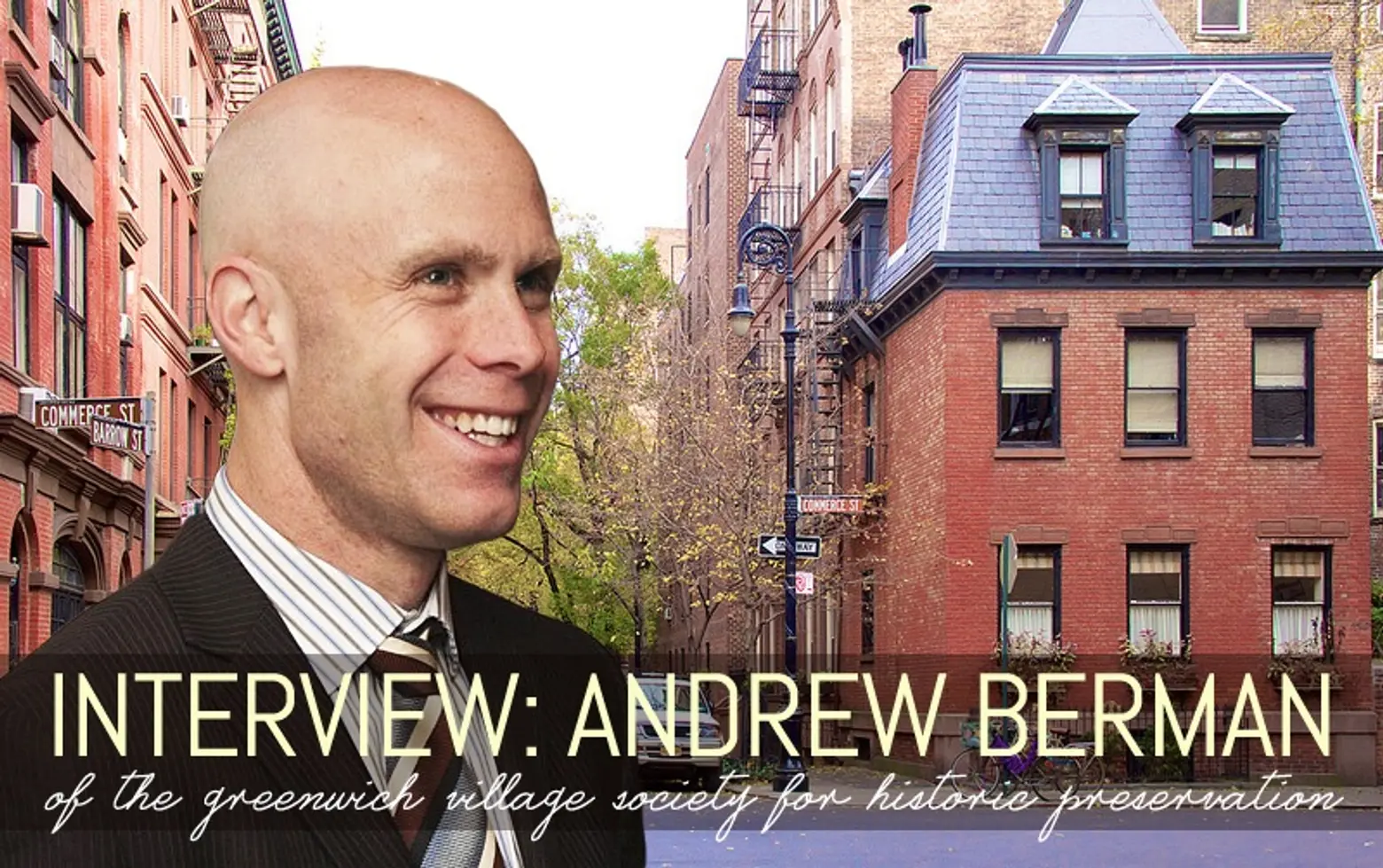

INTERVIEW: Andrew Berman, Executive Director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

There’s been a lot of controversy around preservation in New York City as of late, and through it all, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (GVSHP) seems to always make its voice heard. From debunking myths about affordable housing and historic districts to advocating for the Village’s next great landmark, GVSHP remains on the front lines of the field.

Founded in 1980 to preserve the architectural heritage and cultural history of the Village, the organization now includes the East Village, South Village, Far West Village, Noho, and Meatpacking District in its purview. Part of the reason for GVSHP’s expansion stems from the tireless efforts of its longtime Executive Director, Andrew Berman. Since 2002, he has overseen the research, educational programming, and advocacy of one of the city’s leading preservation nonprofits. We recently sat down with Andrew to learn more about his views on the current state of preservation in the city and where he hopes to take GVSHP in the future.

How did you get into preservation?

Andrew: Growing up in New York, it was always a love of mine. I was imbued with a sense of history of the city, partly stemming from my parents who also grew up here, and from going to a citywide high school. In college, I studied art history and focused on architecture. Then, when I worked for State Senator Thomas Duane, I focused on land use and preservation, especially on the West Side.

GVSHP is one of the most vocal of New York City’s preservation organizations. Was that a goal of yours when you first started at the organization?

Andrew: Yes, definitely; forceful advocacy was a priority for me and for the Board. With rest estate pressure increasing exponentially in the Village, preserving the qualities of the neighborhood became very essential.

Andrew Berman leads a GVSHP rally against the NYU 2031 plan, images courtesy of GVSHP

Andrew Berman leads a GVSHP rally against the NYU 2031 plan, images courtesy of GVSHP

You don’t live in the Village, but what personally connects you to the neighborhood?

Andrew: There are two things. Physically, it’s incredibly beautiful; it’s this intimately scaled amalgam of 19th and 20th century architecture that amazingly has stayed intact and preserved for over 200 years. And then there’s the culture that has been a breeding ground for so many wonderful movements in terms of arts, literature, politics, social change, and music, all of which I really admire. It doesn’t matter where I live or end up, I’ll always feel a strong sense of connection to the Village and what it represents.

GVSHP recently published a report outlining how more than 20 historically significant buildings have been heavily altered or altogether demolished over the past 12 years after city officials gave advanced word to owners that their buildings were under consideration for landmarking. What are some of your suggests for how to solve this issue?

Andrew: It’s very easily solved. The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) needs to go back to doing things how they did for their first 35 years, following the law which says property owners are notified when their building is calendared (calendaring refers to the act of adding a building or district to the LPC’s official hearing schedule) and invited to participate in any public hearings. But they need to end the practice of reaching out to property owners and developers months in advance of taking any formal action to simply say, “we’re thinking of possibility considering your property for landmarking,” because for that significant minority of owners who don’t want to be landmarked it’s a tipoff, and they will use it as they have in the past to obtain permits to either alter or demolish the property.

The other simple suggestion is in response to the related problem that the commission has a 40-day window after calendaring a building within which they can take action, but sometimes they don’t act quickly enough when an owner seeks to demolish or alter their building. The commission should always be in a position to move within 40 days.

The Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) has spoken out a lot lately against landmarking, and recently made a claim that designating historic neighborhoods limits affordable housing. What are your feelings on this?

Andrew: Landmark designation covers only about 3% of the city and prevents or makes it difficult for buildings to be demolished. Many landmarked buildings have affordable housing in them, which by virtue makes them easier to hold onto. Even under Mayor de Blasio’s outline for affordable housing, he recognizes that the single biggest thing is to “preserve and protect the affordable housing we have,” which has been disappearing at such an alarming rate. So, the solution is not to replace every unit we lose, but stop the loss. In that respect, landmarking, if anything, has a positive effect, not the negative one that REBNY claims.

The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street Rafael Chamorro via photopin cc

Mayor de Blasio appointed Meenakshi Srinivasan as the LPC Chair earlier this year. What do you hope she will accomplish that her predecessor may not have?

Andrew: In terms of specifics, we have a few things on the agenda. We want to see the third and final phase of the proposed South Village Historic District, which is the section south of Houston Street, designated. We were able to get part of the East Village designated in 2012, but a lot of the neighborhood that merits landmarking still doesn’t have it, so we’d like to see that expanded. The University Place and Broadway corridors in the Central Village are also almost entirely lacking in landmarks protection, and we’d like to see that change.

Under the prior administration, the LPC established a policy where when an applicant’s proposal isn’t accepted in its initial form, they’re give the opportunity to come back with a revised design, which is then not subject to the public hearing process. Quite often these are the applications approved, without hearing valuable feedback from the public.

Finally, we’d like the Commission to pay more attention to cultural landmarks. Many sites significant to LGBT history and the gay rights movement are located within the Greenwich Village Historic District, but they’re not noted in the designation report. In the case of the Stonewall Inn, the riots took place two months after the designation. Other events happened just prior and weren’t’ recognized as the historically significant events we see them as now. We’d like to see this corrected, so the records accurately reflect their importance and ensure they’re protected in a way that recognizes their extreme significance.

186 Spring Street and a GVSHP-led press conference outside the building, courtesy of GVSHP

186 Spring Street and a GVSHP-led press conference outside the building, courtesy of GVSHP

Speaking of LGBT history, in 2012 you advocated for the preservation of 186 Spring Street based on its social importance to the neighborhood—some of the most important LGBT activists of the 1970’s lived and worked there. How do you feel landmarking should toe the line between architectural and cultural significance?

Andrew: It’s challenging in terms of landmarking because it regulates what you are physically preserving. The Charlie Parker Residence and the Louis Armstrong House have successfully done it because of the people associated with them. I think typically the question is how much does the structure look like what it did during the significant events and how much does the look relate to those historically significant events. In the case of 186 Spring Street, which was a real nexus of activity in the post Stonewall gay rights movement in New York, the building was largely unchanged from its period of significance and not much had changed from when it was built in the 19th century, which spoke to how the building had evolved over time.

3 West 13th Street courtesy of Park Property Advisors

3 West 13th Street courtesy of Park Property Advisors

It’s a common misconception that preservationists hate all modern architecture, and of course we know that’s not true. What’s your favorite contemporary building in the city?

Andrew: I do think that’s a misconception; preservationists have a great deal of respect for modern architecture that’s done well. In the last 10/15 years we’ve seen some good examples of new modern buildings going up in Soho, Tribeca, and the Ladies Mile Historic Districts where the architects did a good job of reinterpreting and updating the contemporary take on a loft building. One example is 3 West 13th Street by Avi Oster Studio– it’s largely glass and metal, but it fits in with the historic buildings discreetly while contrasting them in a respectful way.

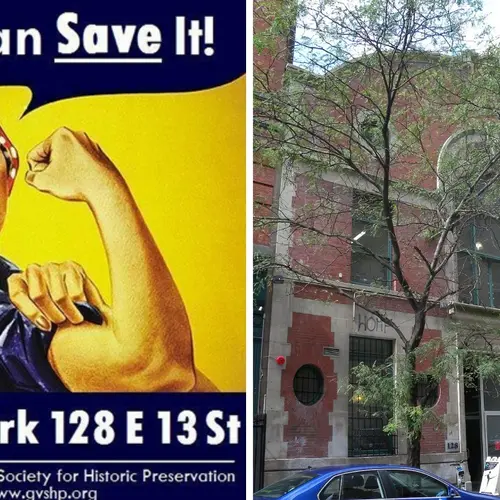

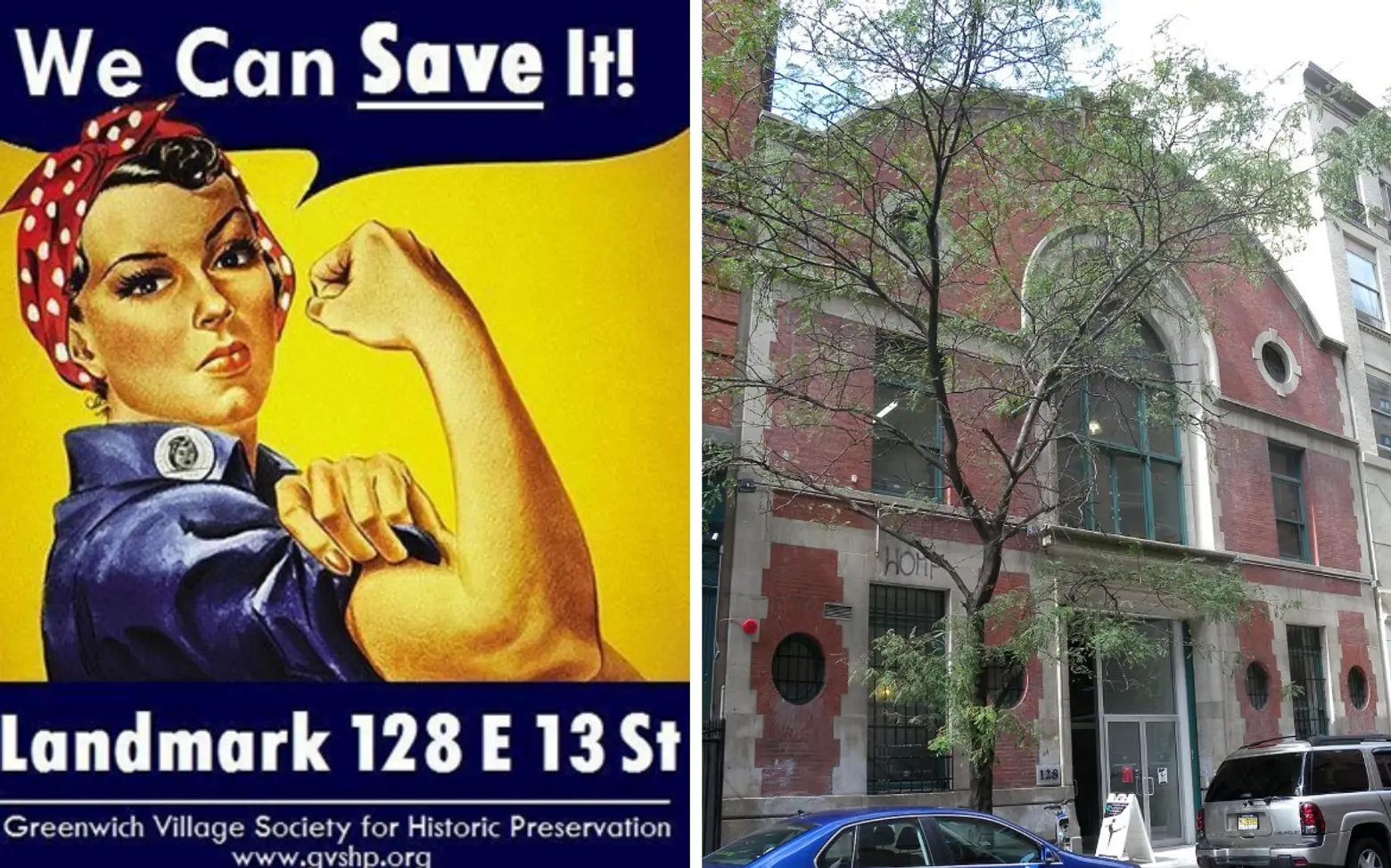

GVSHP’s Rosie the Riveter icon and 128 East 13th Street, courtesy of GVSHP

GVSHP’s Rosie the Riveter icon and 128 East 13th Street, courtesy of GVSHP

GVSHP has had countless victories preserving the architectural and cultural history of the Village. And while I’m sure you don’t like to pick favorites, is there one success that is especially meaningful to you?

Andrew: Yes, there’s two. The South Village Historic District was designated at the end of last year, and it was particularly meaningful for a variety of reasons. There’s so much cultural history there. We managed to get several NYU buildings included within the district that the city initially excluded. This will prevent a 300-foot-tall dorm from being built on Washington Square South. And finally, it was very clear that the city was not going to approve the district, but we used the leverage we had with the Hudson Square rezoning and demanded that the City Council not approve the rezoning unless the South Village designation moved ahead because changes to Hudson Square would have impacted the neighborhing South Village.

The other one is the Van Tassell and Kearny Horse Auction Mart at 128 East 13th Street. It was days away from the wrecking ball, and we rushed to the LPC and urged them to act quickly. They did calendar it quickly, but it took six years to landmark. The building’s history is so unique and reflective of the development of the neighborhood. It started as place where horses were sold to wealthy families, and then when the East Village became gritty and industrial, it was used as an assembly line training school for women during WWII. That’s why we used the Rosie the Riveter image as an icon for the preservation campaign. And in the 1970’s it served as Frank Stella’s studio. How many building have those three incredibly different but rich layers of history?

[This interview has been edited]

Lead image background:Kenneth J. Garcia cc