The backstory on backhouses: How NYC’s hidden rear residences came to be

Via Wiki Commons

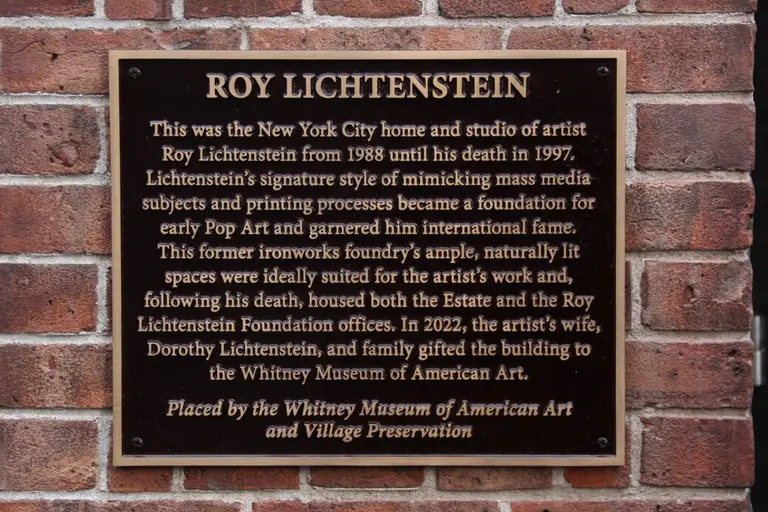

New York City is full of hidden surprises that even the most dyed-in-the-wool New Yorker may not know about. One such example is the elusive “backhouse” or rear house. There are literally scores of these hidden structures throughout the older neighborhoods of Lower Manhattan like Greenwich Village and the East Village. But because they are generally invisible from the street, they’re typically virtually unknown to anyone other than their residents and immediate neighbors. But these oft-romanticized structures have a complicated and surprising history, one which belies their almost mythical place in the psyche of New Yorkers.

At this Brooklyn Heights house, you can clearly see the carriage house in the rear. Photo via a previous listing.

First, definitions: Backhouses are residential structures that are separate from and located behind other buildings (usually, but not always, residential buildings). Backhouses, therefore, don’t have direct entrances off the street. Typically one has to go through the front building, then through a rear courtyard, to get to the backhouse; other times there is a narrow passageway or even a tunnel alongside or through the front building which leads to the backhouse behind.

So how did these structures come about? The classic and seemingly most loved example is the carriage house located behind an elegant early rowhouse. In these cases, a single-family house was built, typically in the early 19th century, with a stable for the family’s horses located behind, accessible through either a side passageway or a tunnel or “horsewalk” through the house. As horses began to disappear from regular use in the city, these stables were often converted to residences, sometimes called carriage houses. Because of the unconventional nature of these spaces, and because the structures sometimes had raw open space or large openings from their prior incarnations, they often attracted artists for whom these types of living and working conditions were ideal. In other cases, they may have attracted artists simply because such space was cheap and acceptable to them, whereas it may not have been for the general public.

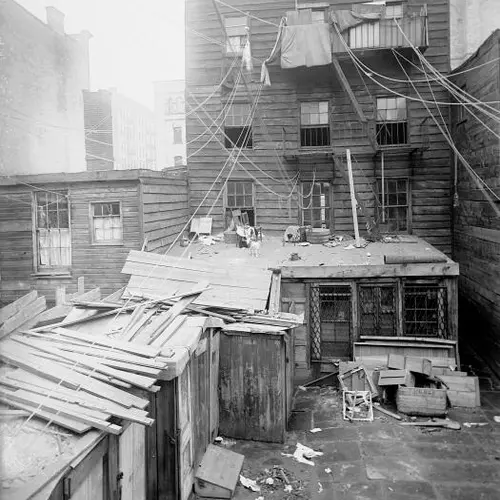

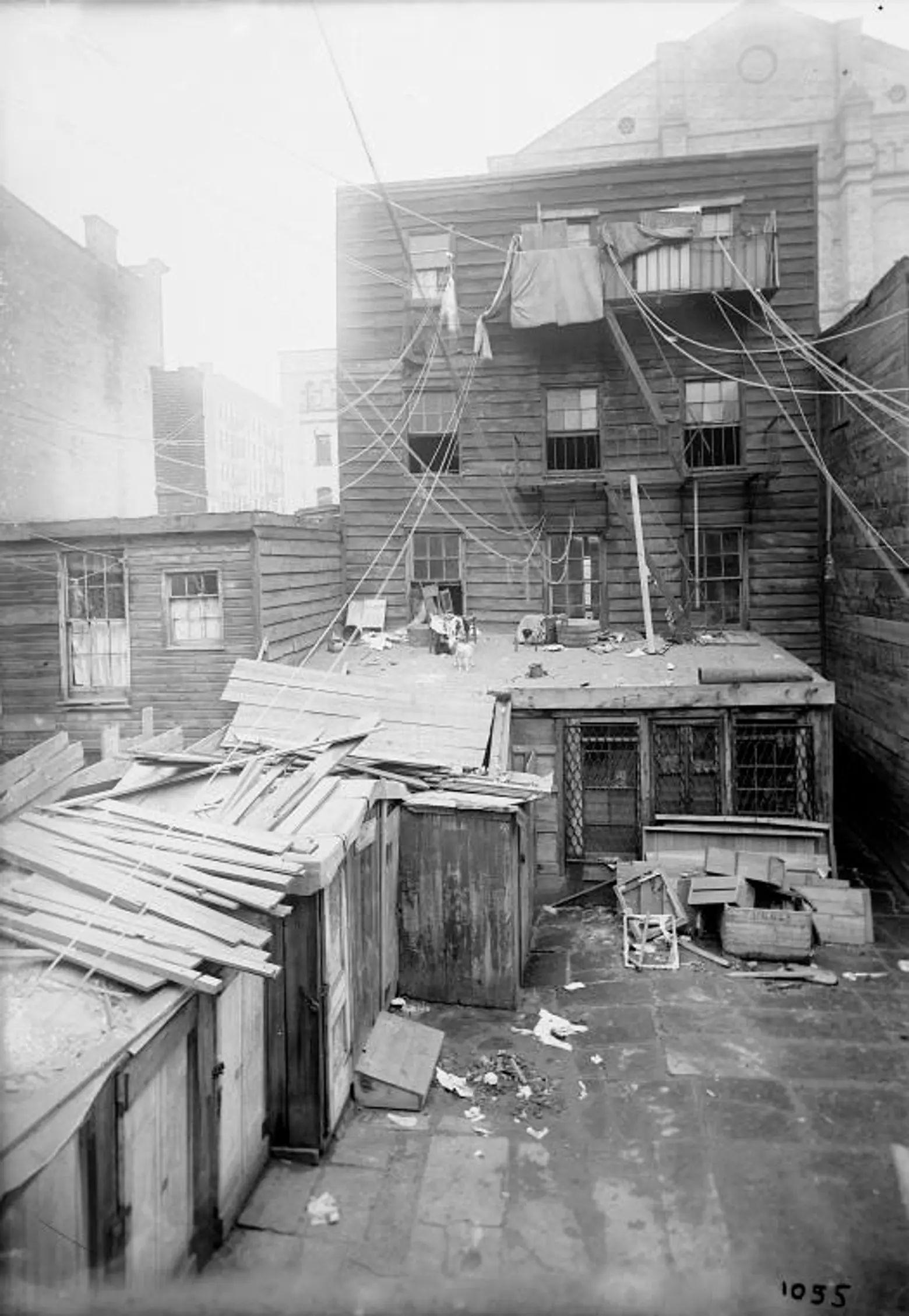

An early 20th-century tenement backyard with several outhouses, via NYPL

An early 20th-century tenement backyard with several outhouses, via NYPL

Most backhouses, however, had less romantic origins. Oftentimes backhouses were built behind tenements or “tenementized” rowhouses (houses which were split up and converted to multi-family dwellings) as a way of simply squeezing more living units into the tiny amount of available land. Thus, sometimes they had windows with little light or air, as they were often mere feet from the walls or windows of the front house or tenement or neighboring buildings. Typically these were built as neighborhoods such as the Village or East Village became awash with immigrants, who paid low rents but were squeezed by the dozens into tiny spaces with sometimes unimaginably challenging living conditions. Unlike the “classic” example cited above, these backhouses usually had several units, even though the buildings themselves were tiny, and could be built up as tall as the front structure, sometimes four or five stories in height.

Unlike their more romantic cousins, these backhouses had less genteel origins, starting life as sheds, utility structures, and in some cases even outhouses. As housing laws and rising expectations for living standards reduced the occurrence of outhouses for residences in New York City, these structures were often built upon or added to and converted to small backhouse housing units.

A Google Earth aerial view of the block bounded by 12th and 13th Streets, 1st Avenue and Avenue A shows multiple backhouses in the center of the block

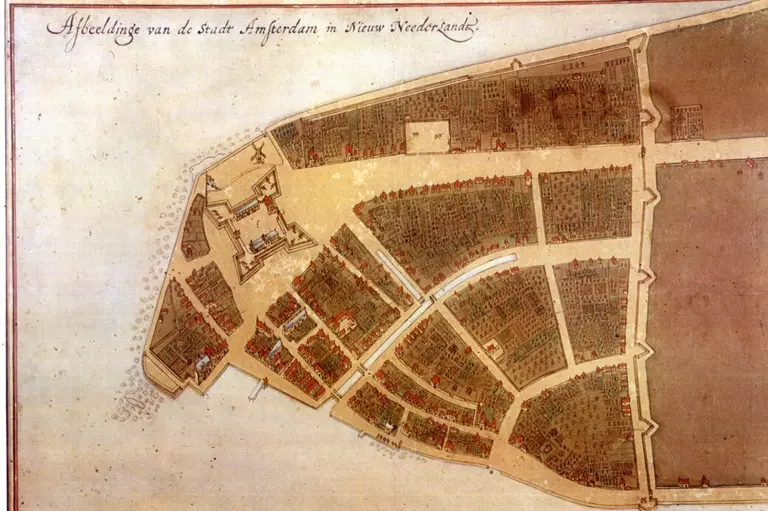

Sometimes, however, backhouses were built as shoehorned-in residences right along with the tenement they were located behind. For example, the four-story front-buildings at 425 and 429 East 12th Street, between 1st Avenue and Avenue A, were both built in 1852, and appear to be very early, purpose-built tenements (i.e. they were built as tenements, not structures built as single-family homes which were converted to multi-family housing ). While experts believe that the earliest purpose-built tenements appeared in New York City in the 1820s or ’30s, these were rare, and by far the majority of tenements were not constructed until after the Civil War when immigration to New York City increased exponentially. In this case, based upon research conducted by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, it appears that the four-story backhouses behind these tenements were built at the same time as the front structures, as opposed to the other scenarios previously described which appear to be more typical.

Exactly why these were built with separate front and rear residential structures, as opposed to the seemingly more efficient arrangement of a single, larger footprint structure as was common with later tenements, is unclear. One theory might be that early tenements seemed to basically mimic the form of single-family houses on the exterior, covering only about 50 percent of the lot and rarely rising more than four stories. Perhaps the conventional expectation that these still-relatively rare (and generally looked down upon) structures would at least look like a house pushed builders to use this two-building form, mimicking a house with a rear structure that was either added later or grew from a pre-existing non-residential structure, rather than the single, larger footprint tenements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was also one way of giving a little more light and air to the residents of these structures, as opposed to building a single long structure with only one set of windows in the front and back. Ironically, though, because these backhouses were often built flush up against the rear of their property lines, they typically blocked light and air to neighboring structures.

Google Street View of the backhouse behind 275 Mott Street, visible over the wall of the old St. Patrick’s Cathedral

So how do you get to see a backhouse, if you’re not lucky enough to live in or next to one? Demolition of adjacent structures is one way; the backhouses as 425 and 429 East 12th Street, for instance, were briefly visible earlier in this decade when adjacent structures were demolished to make way for new construction (which has since obscured them from public view again). Churchyards of school yards or other open spaces are another way. If you look over the wall of the Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry and Mott Streets north of Prince Street, you can see the backhouse behind 275 Mott Street. Beyond that, Google Streetview’s aerial function can offer a bird’s eye view of backhouses, but only if you can spot them or know where to look for them.

Finally, if you’re walking down a street in Lower Manhattan and see a gate with a narrow alleyway next to an older building, or a second doorway within a building with slightly different address than the main one, with “1/2” added at the end, this may well be an entryway to a backhouse. Take a look – you never know what you might find.

RELATED:

- Off the grid: The little Flatiron Buildings of the Village

- What lies below: NYC’s forgotten and hidden graveyards

- Artist aeries: Touring downtown’s ‘studio windows’

+++

This post comes from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Since 1980, GVSHP has been the community’s leading advocate for preserving the cultural and architectural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and Noho, working to prevent inappropriate development, expand landmark protection, and create programming for adults and children that promotes these neighborhoods’ unique historic features. Read more history pieces on their blog Off the Grid