Skyline Wars: Accounting for New York’s Stray Supertalls

Carter Uncut brings New York City’s latest development news under the critical eye of resident architecture critic Carter B. Horsley. Ahead, Carter brings us his eighth installment of “Skyline Wars,” a series that examines the explosive and unprecedented supertall phenomenon that is transforming the city’s silhouette. In this post Carter looks at the “stray” supertalls rising in low slung neighborhoods.

Most of the city’s recent supertall developments have occurred in traditional high-rise commercial districts such as the Financial District, the Plaza District, downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City. Some are also sprouting in new districts such as the Hudson Yards in far West Midtown.

There are, however, some isolated “stray” supertalls that are rising up in relatively virgin tall territories, such as next to the Manhattan Bridge on the Lower East Side and Sutton Place.

Tallness, of course, is relative and some towers of considerable height in low-rise neighborhoods have been distinguished sentinels, such as One Fifth Avenue, the Art Deco apartment building on the southeast corner of Eighth Street that dominates the Washington Square Park cityscape, the 623-foot-high Trump Palace on the southeast corner of Third Avenue at 69th Street, or the 35-story Carlyle Hotel at 35 East 76th Street at Madison Avenue.

Other lonesome “talls” have gotten “crowded” such as the green-glass Citibank tower in Long Island City, which is now getting numerous neighboring towers, and the 541-foot-high Ritz Tower on the northeast corner of 57th Street at 465 Park Avenue, very near 432 Park Avenue.

A New York Times article by Joseph P. Fried about 45 East 89th Street noted that “to those who like their skylines fairly even and orderly, the new structure will no doubt seem a jarring blockbuster,” adding that “but to those who feel that sudden interruptions and jagged variety lend a sense of excitement to a skyline, the Madison Avenue building will be a welcome addition.”

The reddish-brown brick tower is currently replacing its many piers of balconies and its plazas are among the windiest in the city. Critics Norval White and Eliot Willensky declared it a “blockbuster” and wrote that it was “a state of affairs that can’t be condoned, regardless of other virtues.”

Some supertalls are also beginning to significantly augment some previously relatively isolated tall centers such as the New York Public Library area and Madison Square Park.

But the most dramatic of these “stray” supertalls is just to the north of the Manhattan Bridge where Extell Development has started construction at 250 South Street; It is known as One Manhattan Square.

Rendering of One Manhattan Square’s driveway and basket-weave glass façade with Manhattan Bridge in the background

Rendering of One Manhattan Square’s driveway and basket-weave glass façade with Manhattan Bridge in the background

In recent years, Extell has become one of the city’s most active and aggressive developers. Its development of One57 inaugurated the current generation of very tall towers, including their construction of 217 West 57th Street further to the west—this will be the tallest of the city’s current crop at 1,522 feet (roof height).

Ariel East is a 400-foot-high apartment tower at 2628 Broadway designed by Cook & Fox in 2007 for Extell Development

Ariel East is a 400-foot-high apartment tower at 2628 Broadway designed by Cook & Fox in 2007 for Extell Development

In 2007, Extell Development erected two tall, mid-block, apartment houses across from one another on Broadway between 98th and 99th Streets. Both were designed by Cook & Fox but were quite different in site orientation, massing and facades. The taller of the two was Ariel East, a 400-foot-high, 38-story with 64 condominium apartments at 2628 Broadway with an east/west tower orientation. The reflective glass façade was highlighted by broad maroon stripes, several setbacks on its west side, and dark spandrels on its east side. Ariel West is a 31-story tower at 2633 Broadway with 73 apartments and a north/south slab orientation.

A January 2013 article by Robin Finn in The New York Times noted that “Ariel East and its chunky sister tower, Ariel West, preside as the neighborhood’s only bona fide skyscrapers,” adding that “because their installation on an otherwise low-rise horizon provoked a hue-and-cry from preservationists and traditionalists, they will never be replicated; revamped zoning regulations prohibit future towers in the area.”

In his “Streetscapes” column March 2010 in The Times, Christopher Gray wrote that Ariel East and Ariel West were “tall, squarish, glassy towers with maroon trim [and] these are the buildings that West Siders love to hate, out of scale with the neighborhood and way too fancy, so it is said.”

Mr. Gray, one of the greatest architectural historians in the city’s history, however, wrote that he did not hate them: “Me, I like them. Is the stodgy, slightly worn-out quality of the West Side so fragile that it cannot accept a couple of mirror-glass lightning bolts? Extell has also taken what was once a dodgy block and flooded the zone by building the two structures.”

Rendering of Extell tower planned for 252 South Street on the Lower East Side and known as One Manhattan Square (left) and JDS’ tower planned for 247 Cherry Street (right)

Rendering of Extell tower planned for 252 South Street on the Lower East Side and known as One Manhattan Square (left) and JDS’ tower planned for 247 Cherry Street (right)

Extell’s foray into the Lower East Side did not go unnoticed. JDS Development has just disclosed that they are planning an even taller project also near the Manhattan Bridge, a 900-foot-high, 77-story rental apartment tower at 247 Cherry Street. It will have a 10,000-square-foot retail base and 600 rental apartments, about 150 will be permanently affordable. The Cherry Street site is owned by the Two Bridges Neighborhood Council and the Settlement Housing Fund and JDS is acquiring 500,000 square feet of development rights from those organizations for $51 million. A rendering indicated that its façade will have green terracotta cladding. JDS is also developing the 1,438-foot-tall tower at 111 West 57th Street and 9 DeKalb Avenue in Brooklyn, two major supertalls; all three projects have been designed by SHoP Architects.

11 Madison Avenue (left) Metropolitan clock tower (left center) 45 East 22nd Street (center) and One Madison at 23 East 22nd Street (left)

11 Madison Avenue (left) Metropolitan clock tower (left center) 45 East 22nd Street (center) and One Madison at 23 East 22nd Street (left)

Madison Square Park, of course, is a classic New York City development hodge-podge. Its glorious early 20th century roots were established with Napoleon Le Brun’s magnificent 50-story clock tower headquarters for Metropolitan Life (the world’s tallest when completed in 1909), Daniel Burnham’s world-famous Flatiron Building, Cass Gilbert’s Gothic gilded pyramid skyscraper for New York Life Insurance Company on the northeast corner of Madison Avenue and 26th Street, and the splendid Appellate Division Courthouse on the northeast corner at 24th Street.

Those fine assets were tarnished a bit by the beige-brick apartment house at 10 West 22nd Street directly across Broadway from the Flatiron Building and perhaps the world’s greatest site for a mirrored-glass façade. The Rudins then dulled the park’s luster with its rather routine, bronze-glass office tower at 41 Madison Avenue on the southeast corner at 26th Street.

To complicate this urban setting further, Slazer Enterprises, of which Ira Shapiro and Marc Jacobs were principals, commissioned a modern intrusion obviously inspired by Santiago Calatrava’s never-built 80 South Street project near the South Street Seaport in Lower Manhattan where. Calatrava envisioned ten multi-story townhouses in the air jutting out from a vertical core.

Slazer’s architects, CetraRuddy, did a nice variation on Calatrava’s famous unbuilt tower, but its protruding “boxes” mostly contained numerous apartments each, cantilevered on north and east facades introducing a slight case of wobbly asymmetry to the park. The dramatic and very slender residential skyscraper on the south side of Madison Square Park at 23 East 22nd Street has about 69 apartments and is known as One Madison. Although some observers were a bit concerned that this tower was impinging upon the space of the majestic Metropolitan Life Insurance Company tower, other observers were impressed by its sleek façades and vertiginous verticality.

The Slazer project was eventually taken over by the Related Companies but not before it abandoned a mind-boggling addition designed by Rem Koolhaas of a “peek-a-boo” brother building on 22nd Street that was cantilevered in steps to its east, and featured windows that looked not only east and north but also downwards. Koolhaas is best-known for his book, “Delirious New York” in which the cover illustration showed the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building cozily in bed with one another. His “peek-a-boo” design was startling and, while very ungainly, incredibly memorable.

The CetraRuddy tower extends through to 23rd street where it is next to a McDonald’s that is the best looking storefront on that block. The tower’s entrance, however, is a low-rise base with vertical grills on 22nd Street that has nothing to do with the tower’s setback design but is still quite handsome. It is all the more interesting because it is very different from another new low-rise base on the same block for another setback tower, now in construction at 45 East 22nd Street.

Rendering of 45 East 22nd Street

Rendering of 45 East 22nd Street

45 East 22nd Street is being developed by Ian Bruce Eichner, who built CitySpire at 150 West 56th Street that for a while was the tallest mixed-use building in Midtown. For this 777-foot-high project, Eichner commissioned Kohn Pedersen Fox, the architect of One Jackson Place in Greenwich Village and some supertalls in China. Its glass-clad design rises from a five-story base on 22nd Street that is an extremely handsome structure with broad expanses of granite and rustication. The tower also flares at the top in a fashion similar to the design of another tall residential tower at 50 West Street downtown, also now in construction. The 65-story tower will have 83 condominium apartments and will be the tallest around Madison Square Park when finished.

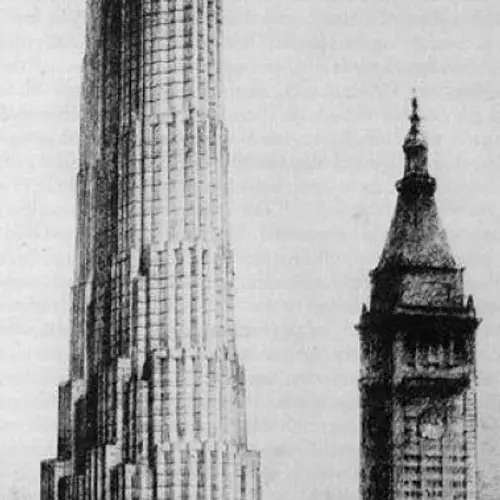

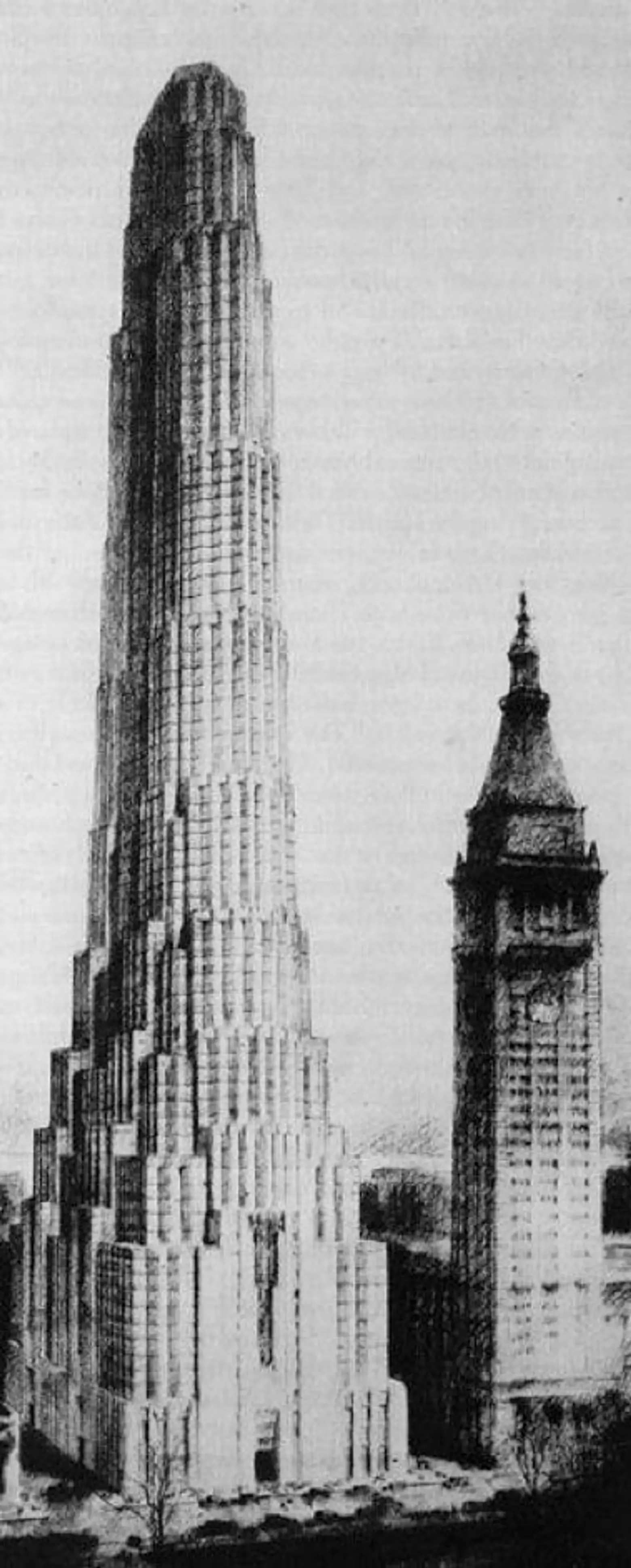

Rendering of 11 Madison Avenue (right) just to the north of the Metropolitan Life clock tower, right, shows setback scalloped plan by Harvey Wiley Corbett and Dan Everett Waid for 100-story building on which construction was stopped at the 29th floor because of the market crash in 1929.

Rendering of 11 Madison Avenue (right) just to the north of the Metropolitan Life clock tower, right, shows setback scalloped plan by Harvey Wiley Corbett and Dan Everett Waid for 100-story building on which construction was stopped at the 29th floor because of the market crash in 1929.

In their brilliant book, “New York 1930, Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars,” authors Robert A. M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin and Thomas Mellins, provide the following commentary about 11 Madison Avenue:

- “In 1929 Harvey Wiley Corbett, in association with Waid, prepared plans for various versions of a telescoping tower, the height of which ranged from 80 to 100 stories. The tower, which was Corbett’s most visionary design, was meant to be the world’s tallest. The walls folded rhythmically into triangular bays, which Corbett hoped to realized in metal and glass, despite the city’s building code’s insistence on masonry construction. The tower would have echoed both the fluted stone shaft of Ralph Walker’s Irving Trust Building and the crystalline glass skyscrapers proposed by Hugh Ferriss. Escalators would have provided access to the first sixteen floors, thus reducing the size of the elevator cores without sacrificing the quality of service on the upper floors. The Depression forced the company to curtail its plans; the building realized was essentially the base off the planned tower, its clifflike masses clad in limestone. Waid and Corbett’s design was built in three stages, the first of which, facing Fourth Avenue, was completed in 1933. According to Corbett, the new headquarters was ‘not a show building from the general public’s point of view. In fact, it is a highly specialized building designed primarily as a machine to do as efficiently as possible the particular headquarters work of our large insurance company.’ Eighty-foot-deep floors were made possible by full air-conditioning, and indirect lighting increase in intensity with the distance from windows. The acoustic-tile ceiling stepped up in six-inch increments from a low point near the core to just about the windows, providing ample duct space with minimum loss of natural light. Aside from its sheer vastness and the community like aspects of the facilities for work, eating and recreation that it housed, the principal interests of the design lay in the building’s unusual shape and in its monumentally scaled street-level arcades and lobbies. The monumental lobbies were planned to accommodate the 25,000 workers expected to inhabit the fully expanded building.”

In August 2015, it was noted that SL Green Realty had closed on its $2.6 billion purchase of 11 Madison Avenue from the Sapir Organization and minority partner CIM Group.

As reported by The Real Deal, “The deal, the largest single-building transaction in New York City history, is a huge coup for Sapir, which bought the property in 2003 for $675 million and managed to bring in marquee technology and media tenants….The 2.3 million-square-foot Art Deco skyscraper, located between East 24th and 25th streets, has tenants such as Sony, which is taking 500,000 square feet at the top of the 30-story tower, and Yelp, which is taking over 150,000 square feet. Anchor tenant Credit Suisse also renewed its lease at the tower last year, but downsized to 1.2 million square feet to make room for Sony. Talent agency powerhouse William Morris Endeavor is taking about 70,000 square feet. The $2.6 billion purchase price—which includes about $300 million in lease-stipulated improvements—is the second-highest ever paid for a New York City office tower after Boston Properties’ $2.8 billion purchase of the GM Building, at 767 Fifth Avenue in Midtown, in 2008. It is also the largest single-building transaction in the city’s history, as the GM Building deal was part of a $3.95 billion package that included three other towers.”

What is astounding, since the supertall era had begun, is that the Sapir Organization and CIM did not build out Corbett’s tower as the foundations were in place to add 60 or so stories to the existing building. Granted that might have interfered with Sony’s inexplicable move out of the former AT&T building on Madison Avenue between 55th and 56th Streets, but surely Sony could have found alternative spaces given the current building boom.

Rendering of proposed tower at 1710 Broadway on northeast corner at 54th Street

Rendering of proposed tower at 1710 Broadway on northeast corner at 54th Street

1710 Broadway

C & K Properties, which is headed by Meir Cohen and Ben Korman, acquired the six-story office building at 1710 Broadway on the northeast corner at 54th Street in 2003 for $23 million and proceeded to buy air rights from nearby properties. The building on the site, which is also known as 205 East 54th Street, houses Bad Boy Entertainment, which is run by Sean Combs. In August 2015, it was reported that Extell Development, which is headed by Gary Barnett, acquired a $247 million stake in the site, which could accommodate tower as high as 1,000 feet. Goldstein, Hill & West has been hired as the architect and the firm reproduced the above rendering for the site showing the planned tower across 7th Avenue from the Marriott Courtyard and Residence Inn tower designed by Nobutaka Ashihara.

The Goldstein, Hill & West design is among the most attractive of the city’s current crop of supertalls; a very svelte assemblage of thin slabs with a few setbacks above a base with a large LED sign that wraps around the corner and is framed by angled piers. Its mirrored glass facades also complement those of the hotel across the avenue.

Rendering of 520 Fifth Avenue on the northwest corner at 43rd Street

Rendering of 520 Fifth Avenue on the northwest corner at 43rd Street

520 Fifth Avenue

At 520 Fifth Avenue on the northwest corner at 43rd Street, Gary Handel has designed at 920-foot-high, mixed-use tower for Ceruzzi Properties and the American branch of Shanghai Municipal Investment that will be the tallest tower on Fifth Avenue. It will soar several hundred feet higher than the Salmon Tower at 500 Fifth Avenue on the northwest corner at 42nd Street as well as the very ornate Fred F. French Building nearby on the other side of the avenue and is a block to the west of One Vanderbilt that will be the city’s second tallest at 1,502 feet high across from Grand Central Terminal.

In August 2015 Ceruzzi and SMI paid Joseph Sitt’s Thor Equities $325 million for the property and 60,000 square feet of air rights. Thor had acquired the site for $150 million from Aby Rosen and Tahl-Propp Equities in 2011. Lou Ceruzzi, the CEO of Ceruzzi Properties, revealed that project will have three levels of retail at the base, topped with a hotel of 150 to 180 rooms and luxury condominium apartments.

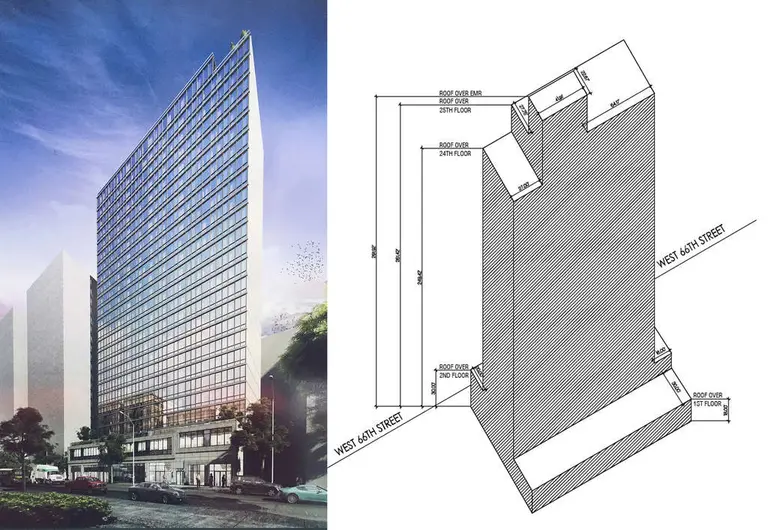

Extell and Megalith are reported to be planning a very tall condo tower at 44 West 66th Street near Lincoln Center

Extell and Megalith are reported to be planning a very tall condo tower at 44 West 66th Street near Lincoln Center

44 West 66th Street

Another new, tall project was recently disclosed for 44 West 66th Street near Lincoln Center on the Upper East Side. As 6sqft reported at the end of April this year, Extell Development and Megalith Capital had assembled a site “with rumors circulating of a possible super tower rising as high 80 stories.”

Moreover, what else known at that point was that in 2014 Megalith purchased three office buildings owned by the Walt Disney Company for $85 million. In July, Extell purchased the adjacent lot, home to the synagogue of Congregation Habonim for $45 million, where they plan to build a soaring condo tower along with Megalith from the combined 15,000 square foot footprint. SLCE is listed as architect of record.

Rendering of 900-foot-high proposed tower at 426-432 East 58th Street designed by Sir Norman Foster for the Bauhouse Group

Rendering of 900-foot-high proposed tower at 426-432 East 58th Street designed by Sir Norman Foster for the Bauhouse Group

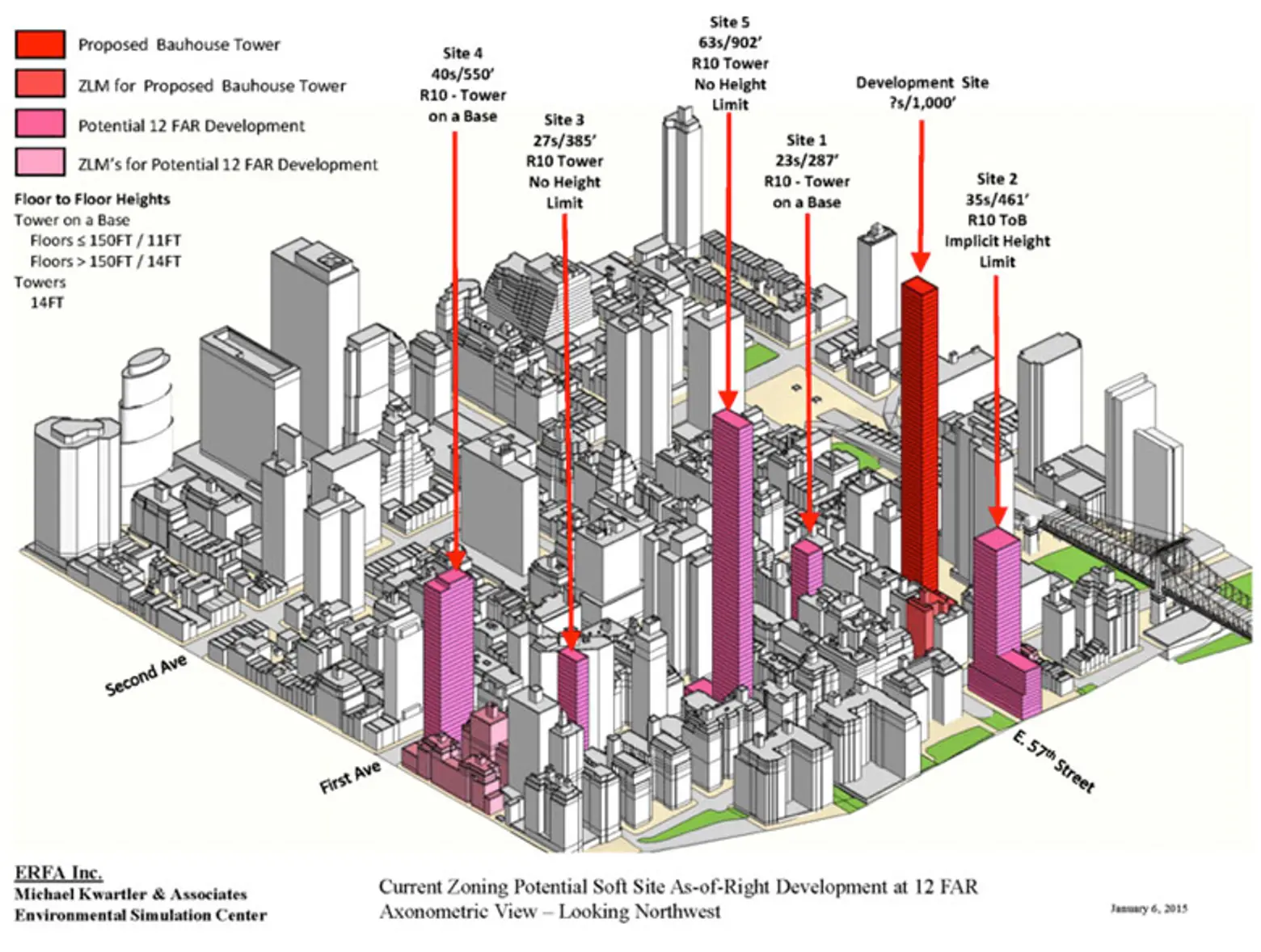

426-432 East 58th Street

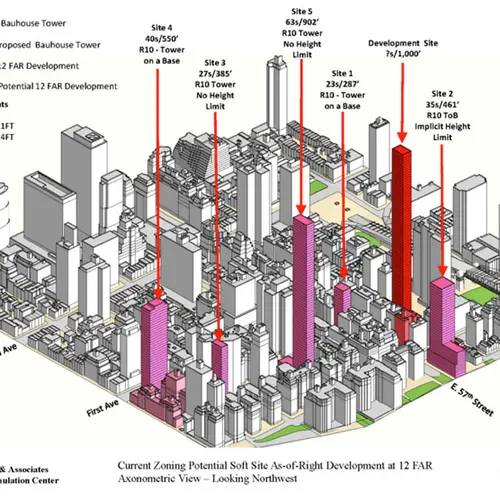

The Bauhouse Group got permits at the end of 2015 to erect a 900-foot-high, Norman Foster-designed residential condominium tower at 426-432 East 58th Street directly across from Sigmund Sommer’s huge, 48-story, staggered slab Sovereign apartment house that extends through to 59th Street and has dominated the Manhattan approach to the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge since it was completed in 1974. The mammoth Sovereign is only half the height of Bauhouse’s tower.

The mid-block Bauhouse tower will be 80 stories high and will contain 115 condominium apartments. Although it is on axis with Billionaires’ Row’s supertalls between Park Avenue and Central Park West and 57th and 60th streets, it really is part of the Sutton Place neighborhood and is a considerable distance from Park Avenue.

It is 10 blocks north of Trump World Tower at 845 First Avenue whose 845-foot-height created a controversy in 2001 with some neighbors like Walter Cronkite for rising several hundred feet above the United Nations Secretariat Building, which was the tallest building along the East River since it was erected in 1950.

In January this year, a group of Sutton Place residents and politicians filed plans for a rezoning that would block the development of supertall towers in that area of town. Known as “The East River Fifties Alliance,” the group formally submitted their plan (drafted by urban planners) for a rezoning of the area bounded by First Avenue and the East River between 52nd and 59th streets to the Department of City Planning. Backers included Senator Liz Krueger, City Councilmen Ben Kallos and Daniel Garodnick, Borough President Gale Brewer and community stakeholders.

The red tower is Bauhouse Group’s planned 900-foot-high tower on 58th Street in this graphic created by the East River Fifties Alliance that wants to prevent the spread of supertalls into its neighborhood. The graphic also shows unannounced tall building on the north side of 57th Street on the townhouse block bounded by Sutton Place and 58th Street, indicated as Site 2.

The red tower is Bauhouse Group’s planned 900-foot-high tower on 58th Street in this graphic created by the East River Fifties Alliance that wants to prevent the spread of supertalls into its neighborhood. The graphic also shows unannounced tall building on the north side of 57th Street on the townhouse block bounded by Sutton Place and 58th Street, indicated as Site 2.

The proposed rezoning for the luxury residential neighborhood would limit height restrictions to 260 feet and require at least 25 percent of new residential units to be affordable.

In their book, “New York 1930 Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars,” Robert A. M. Stern, Gregory Martin and Thomas Mellins recounted that “the unrealized Larkin Tower, proposed for a site at West Forty-second Street between Eighth and Ninth avenues, inaugurated the height race in 1926.”

“A proposal for a building more than 500 feet taller than the Woolworth Building, the Larkin project stunned the city with a telescopic tower that was to rise 1,298 feet and contain 110 stories of offices….’The New York Times’ was horrified by the proposed concentration of 30,000 workers in a project that made ‘the Tower of Babel look like a child’s toy.’” The project did not advance, however, and its site was eventually developed with Raymond Hood’s great McGraw-Hill building, affectionately known as the Green Giant.

The Empire State Building

The most famous “stray” of them all, of course, has been the Empire State Building that was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon in 1931 with its top planned to serve as a mooring mast for dirigibles. The building gained fame quickly as the roost for King Kong and later sprouted a tall antenna. It has lost none of its grandeur but two developments may infringe upon its turf and solitary splendor: a tower designed by Morris Safdie on the site of the Bancroft Building just to the west of the Marble Collegiate Church on Fifth Avenue at 29th Street, and Vornado’s revived plans for a supertall to replace the stately Hotel Pennsylvania across from Penn Station on Seventh Avenue at 32nd Street.

The sanctity of the Empire State Building was recently invoked by Amanda Burden when, as chairman of the City Planning Commission, she lopped off the top 200 feet of Jean Nouvel’s tower next to the Museum of Modern Art on 53rd Street as intruding on the Empire State’s grandeur, an argument not raised since, despite the astounding recent proliferation of supertalls.

+++

Carter is an architecture critic, editorial director of CityRealty.com and the publisher of The City Review. He worked for 26 years at The New York Times where he covered real estate for 14 years, and for seven years, produced the nationally syndicated weeknight radio program “Tomorrow’s Front Page of The New York Times.” For nearly a decade, Carter also wrote the entire North American Architecture and Real Estate Annual Supplement for The International Herald Tribune. Shortly after his time at the Tribune, he joined The New York Post as its architecture critic and real estate editor. He has also contributed to The New York Sun’s architecture column.

IN THE SKYLINE WARS SERIES:

- The Most Important Towers Shaping Central Park’s South Corridor, AKA Billionaires’ Row

- One Vanderbilt and East Midtown Upzoning Are Raising the Roof…Height!

- What’s Rising in Hudson Yards, the Nation’s Largest Construction Site

- In Lower Manhattan, A New Downtown Is Emerging

- Brooklyn Enters the Supertall Race

- As Queens Begins to Catch Up, A Look at the Towers Defining Its Silhouette

- New Jersey’s Waterfront Transforms With a Tall Tower Boom